In Ukraine, its own counterpart of "Roskomnadzor" has appeared, – the Internet regulator of the Derzhspetszviazku

In Ukraine, its own counterpart of "Roskomnadzor" has appeared, – the Internet regulator of the Derzhspetszviazku

If you have come across news such as “State Service of Special Communications and Information Protection (Derzhspetszviazku) has blocked sites advertising Kyiv prostitutes” or “In Ukraine, a website allegedly selling steroids and sports pharmaceuticals has been blocked,” you may have reasonably wondered: is fighting prostitutes and illegal steroid sales really within the purview of this respectable service?

A lawyer from Axon Partners, Mykyta Yevstifeyev, was also quite intrigued by this question. It turned out that blocking websites is just the beginning of a rabbit hole that leads to an attempt to turn the Derzhspetszviazku into a kind of “super-regulator” of the internet during wartime, with nearly unlimited powers and minimal public accountability and transparency. He notes in advance in the publication Dead Lawyers Society: indeed, it is worth worrying.

NCTM

During the war, an internet super-regulator appeared – Derzhspetszviazku

The central figure in this story will be the National Center for Operational and Technical Management of Telecommunications Networks, or “NCTM” for short. The center was created in 2019 and is a structure within the Derzhspetszviazku (although formally it is an independent legal entity). The decisions mentioned at the beginning were made by the NCTM.

The creation of the Center was envisaged by the Law of Ukraine “On Telecommunications” from 2003, from which the relevant norms migrated to the current Law “On Electronic Communications”. The main function of the NCTM in both laws is defined as the operational and technical management of communication networks in conditions of war or emergency, which explains the almost complete absence of any information about this body’s activities until 2022.

Essentially, the NCTM is supposed to act as a “situational center,” temporarily taking over the coordination of certain aspects of the work of communication service providers to ensure stable operation of communication networks, as well as to meet the immediate needs of the state (for example, using these NCTM must follow in its activities.

Another interesting function of the NCTM can be found in the Cabinet of Ministers resolution on the moratorium on fulfilling obligations to legal entities with Russian beneficiaries: the Center is one of the bodies that has the right to sanction exceptions to this prohibition.

Both the Law and the Procedure mention that the NCTM has the right to issue directives that are mandatory for all providers. In the first months after the full-scale Russian invasion, the Parliament strengthened this norm with a sanction: non-compliance with NCTM directives is currently grounds for immediate exclusion of a provider from the Register of Electronic Communications Service Providers and a ban on interconnection of other providers with its networks (which essentially means a complete cessation of its activity).

A pretty serious reason not to question such directives, right? But, it seems, this has become a reason for a rather creative interpretation of the law in the style of “the boundaries of authority end nowhere.”

Block Me If You Can

Attempts to block something on the internet are as old as the internet itself. In Ukraine, they are accompanied by a constant search for extravagant legal constructions: imposing arrest on “property intellectual rights arising in internet users when using a web resource” under the Criminal Procedure Code (decisions with such wording are still in vogue in 2023) or applying sanctions by decisions of the National Security and Defence Council (which are probably based on the fact that the list of possible types of sanctions in the Law is not exhaustive).

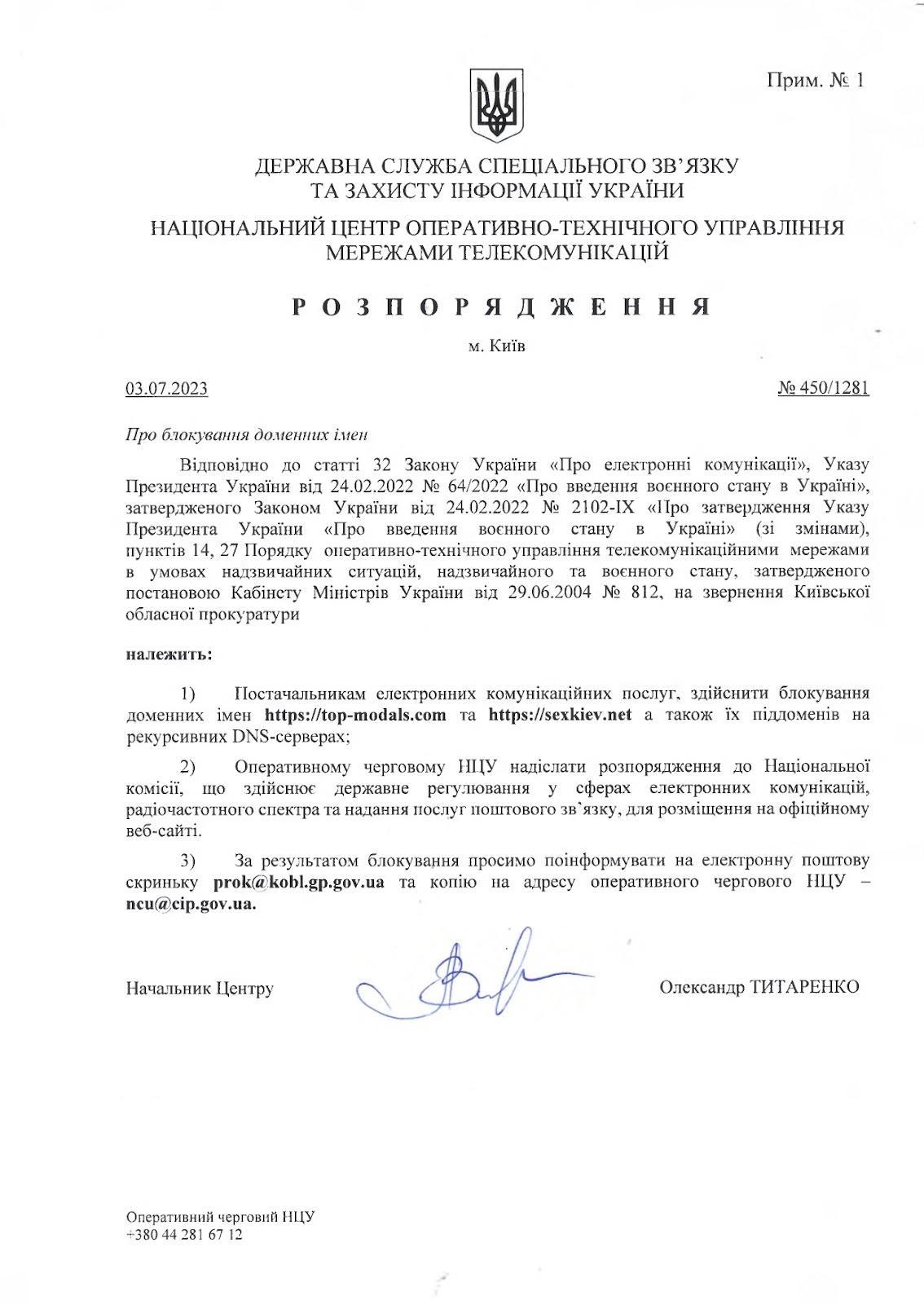

Starting in 2022, NCTM’s directives are included in this collection. Here is an example of such a document dedicated to the issue of the aforementioned Kyiv prostitutes:

In all similar directives (or in all that I could find – more on that later), providers are required to block domain names on their “recursive DNS servers.” This operation, if not sanctioned by a state order, fully deserves the name “petty fraud.” Here’s how it works.

As is known, DNS is a system that stores information about domain names, particularly about IP addresses associated with each domain name. DNS has a hierarchical structure based on a clear assignment of a specific DNS server to a specific zone of address space. There is a “canonical” procedure for obtaining information about a domain name: first, you need to make a request to one of the DNS servers responsible for the root zone (root zone), that is, for the entire address space of the internet.

The root server will direct you to the next level server responsible for a top-level domain (.com, .org, .ua, etc.). This sequence will continue until you receive a response from the final link – the authoritative DNS server for a specific domain name. “Authoritativeness” means that this server has definitive information about the required IP address and does not redirect to another DNS server.

In practice, information about domain names changes relatively infrequently. Therefore, there is no practical sense in going through the complete procedure, which usually has no less than three iterations, every time. Recursive DNS servers are a mechanism designed to optimize this process.

The principle of operation of recursive servers is caching data received from authoritative DNS servers. Imagine that a provider has several thousand clients, and each of them visits the site google.com every day. In theory, each client would have to go through the full procedure each time, although it is very unlikely that Google’s IP address would change during the day. Instead, the provider integrates a recursive server into its network, which makes the full request once a day and then provides each client with the saved information.

This reduces both the time to receive a response and the load on DNS servers that would have to process requests according to the full procedure. (If it seems that optimization is minimal here, it’s not. For example, Google alone is visited about 80 billion times a month, or about 30,000 times per second).

Of course, for this scheme to work, the client needs to be configured to request the default recursive server rather than going through the full procedure. In the case of most household consumers, who likely aren’t even aware of these settings, this poses no problem.

Returning to our directives. In fact, the NCTM requires providers to “manually” substitute correct data about specific domain names on their recursive servers, thereby preventing the obtaining of real information about the IP address of a particular site.

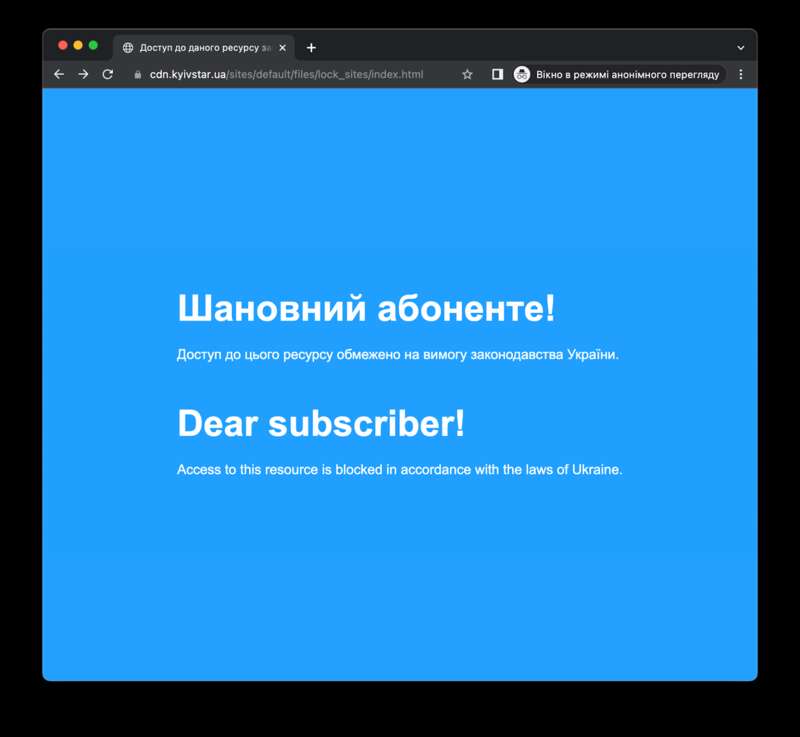

Example: the correct IP address of the domain name top-modals.com, 78.108.184.190, on Kyivstar’s recursive DNS server, is converted to 81.23.24.194. The latter, in turn, leads the user not where they wanted to go but here:

Convenient? But ineffective and, I would say, primitive: to bypass this “blocking,” it is enough to configure the browser to use an external, non-controlled by the Ukrainian government, DNS server (for example, the public Cloudflare server 1.1.1.1 or Google 8.8.8.8).

Secret. Top Secret

Despite this, Ukrainian law enforcement officers (and not only them) have grabbed onto this relatively simple method of “blocking” sites, and already since the second half of 2022 started sending relevant requests to the NCTM. As can be seen from the several hundred NCTM directives on this matter published on the website of the National Commission that carries out state regulation in the fields of electronic communications, radio frequency spectrum, and postal services (NCEC), the most frequent authors of such requests became the Economic Security Bureau, the Security Service, the Cyber Police Department, the National Bank, and several other bodies. Occasionally, the NCTM obliged providers to block something on its own initiative (or perhaps simply forgot to specify the initiator).

Not all issued NCTM directives are published on the NCEC website (by my estimation – about less than 10 percent). The NCTM doesn’t have its website, and, accordingly, we, ordinary curious citizens, are left only with what the NCTM itself deems appropriate to pass on to the NCEC.

Fortunately, we have the Law “On Access to Public Information,” which obliges any subject of authority (which the NCTM is) to respond to requests and publish all legal acts adopted by it. Unfortunately, the NCTM and the Derzhspetszviazku consider it okay to ignore this Law.

For instance, the response of the NCTM to my request for all directives adopted after the start of martial law was extremely concise and hinted that asking about such things was not appropriate. The letter from the Administration of the Derzhspetszviazku to my complaint about the non-disclosure of directives was somewhat more verbose, though its main message did not differ. Interestingly, both responses referred to paragraph 33 of the Cabinet-approved Procedure, which does not mention directives but instead refers to certain “generalized information”:

“33. Generalized information regarding the operational and technical management system of telecommunications networks is information with restricted access.”

Almost the same fate befell my requests to the Economic Security Bureau and the Cyber Police Department regarding copies of their requests sent to the NCTM. Initially, they refused to provide them in principle, and only after a polite nudge from the Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights did they somewhat rethink their position. However, even on the second try, both bodies sent me copies of these requests, having deleted the domain names from them. Explaining what harm they are trying to prevent (such justification is a direct requirement of the Law), these bodies created real masterpieces of bureaucratic epistolary style. Here, for example, is a fragment of the BES argumentation:

“The possibility of causing substantial harm to the protected interests of the BES may lie in the possibility of manipulation of the relevant information, which is information with restricted access, by third unscrupulous parties to create prerequisites for attempts and endeavors to use the activities of the BES in the interests of certain forces, increasing the level of disorganization of the BES’s activities, the increase of risks of pressure (influence) on those involved in performing investigative and operational-search tasks, the increase of risks of the spread of bribery, corruption, and its manifestations in the state, etc. Given the functions and powers of the BES, the likelihood of harm occurring as a result of granting access to the aforementioned information is quite high.”

By the way, despite all the seriousness of the risks, the BES simply closed the domain names (and, for some reason, the surname of MP Zheleznyak) with white rectangles in PDF files, so reading them in the text layer posed no difficulties. The Cyber Police approached the matter more thoroughly, first crossing out the dangerous data with a marker on paper copies and then sending me scans. Although if these domain names were already blocked by the NCTM’s decision, then law enforcement has no reason to worry. Wait, or is there?..

Hanlon’s Razor

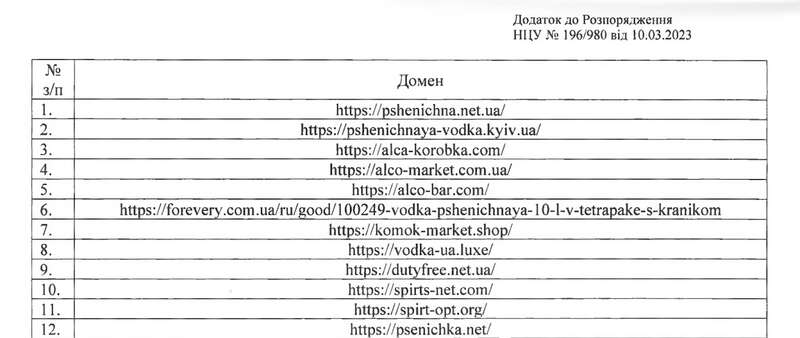

In addition to the “ordinary” requirements for blocking domain names in NCTM directives, you can find various curiosities, such as a requirement to block access to a specific page of a site (directive № 196/980, line 6):

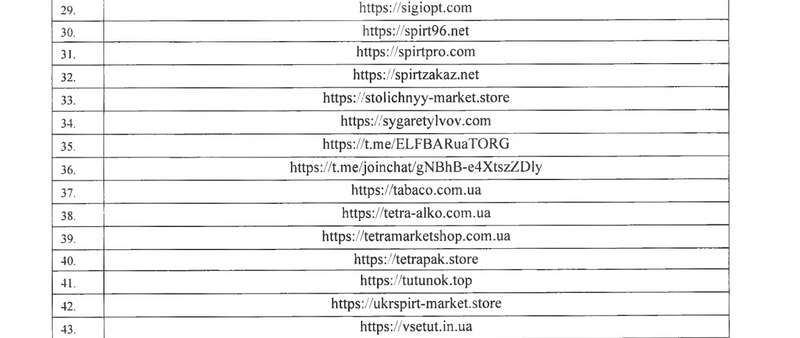

– or to a telegram channel (directive № 184/968, line 35):

(“Oh, was that possible?” must have thought the National Television and Radio Broadcasting Council, which is still looking for ways to influence Telegram.)

Sometimes services that do not engage in any dubious activities themselves come under disfavor: googleadservices.com (directive № 184/968), besplatka.ua (directive № 196/980) or – a very recent example – linktr.ee (directive № 690/1521).

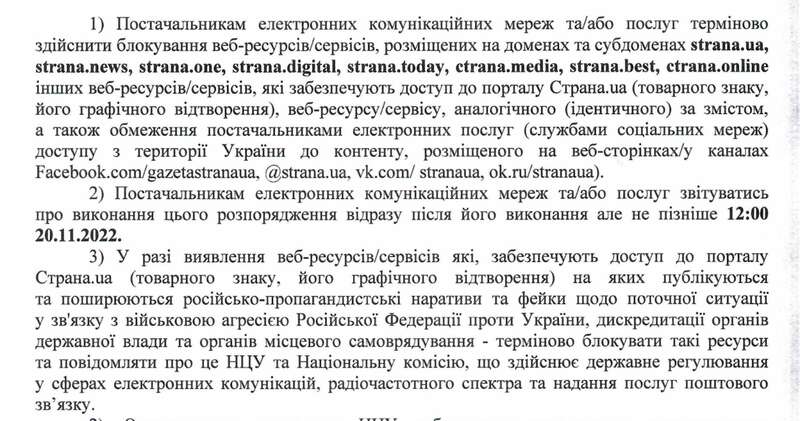

In the examples above, at least you can identify the entity towards which the NCTM attempted to direct its regulatory efforts. But in the “URGENT” directive № 668, it decided to shift this mission to the providers themselves:

I leave it to you to conclude about the sense of mostly unenforceable demands (though I cannot help but mention that one should not attribute to malice what can be explained by sheer incompetence).

Why It’s Worth Worrying

1. I have no doubt that the NCTM can perform (and probably does) valuable functions for the defence of the state. But, like any regulatory tool, the state should use it as intended. One can debate about the relative societal harm of websites offering drugs, sex services, or illegal alcohol for sale – but to me, it is clear that blocking these sites goes far beyond the NCTM’s mandate for “operational-technical management” of networks.

Unfortunately, attempts to use the NCTM for these purposes are another “crutch” to compensate for the lack of a legislatively defined procedure and grounds for blocking access to web resources.

2. No one denies that martial law implies restrictions on rights and freedoms. But for some reason, there is a notion in government circles that such restrictions themselves are unlimited, and any state body can, under the guise of martial law, restrict any right if it deems it appropriate. Reminding such bodies that Articles 8 and 19 of the Constitution continue to apply even during martial law causes them at least some confusion, if not genuine surprise. The situation with the NCTM is one of the many manifestations of this unfortunate trend.

3. Transparency in the work of any regulatory body is the key to trust in its decisions. The total secrecy surrounding the NCTM’s activities works in the opposite direction.

That’s why I filed a lawsuit against the NCTM demanding it to publish all of its adopted directives, and in August, the Kyiv District Administrative Court opened proceedings in the case. Unfortunately, in court, the NCTM continues to insist that its defence-related activities allow it to entirely hide all the acts it issues – not just the information within them that really could cause real harm if disclosed. (After all, we don’t know whether the Center has decided to take over other functions that are uncharacteristic of it and have nothing to do with state defence).

Openness should be the rule, not the exception.

4. When the state – whether in peacetime or wartime – creates a regulatory scheme with serious sanctions, one would expect that its administration is handled by people who at least understand what they are dealing with (and, for example, do a minimal sanity check of the lists sent to them by other bodies, or realize that blocking a webpage or a telegram channel at the DNS level is impossible).

5. All these things are basic safeguards meant to prevent the gradual transformation of wartime expediency into a tool for arbitrary restriction of rights and freedoms. Aversion to arbitrary authority is the quintessence of many centuries of political development of Western civilization, which we aspire to belong to. But stepping onto the slippery slope to authoritarianism is much easier than continuing to struggle for the efficacy of the rule of law.

P. S. All materials mentioned in the article can be viewed on Google Drive at this link.

Mykyta Yevstifeyev, published in the publication Dead Lawyers Society

Topics: State Special Communications ServiceRoskomnadzorUkraineState Service of Special CommunicationsWebsite blocking

Comments:

comments powered by DisqusЗагрузка...

Our polls

Show Poll results

Show all polls on the website